When I was in college in the 1980s, I took a fine art photography course every semester at Yale, once I found out the art department offered them. Some of my best times in those classes were the days when the head of the photography department, Tod Papageorge, shared important kernels of wisdom.

This didn’t happen often, and to be honest, most times in our undergraduate courses, Tod was just going through the motions. We students would arrive a few minutes before class, we would tack up our latest photos on the wall, then Tod would come in, and for ninety minutes, he would lead the critique. Looking back now, I don’t know how he kept it up. Our work was no good. He was an experienced critic, winner of Guggenheim fellowships, an artist with work in the collections of the best museums, with a wealth of background and knowledge to share. Our work wasn’t up to his standard. Most of the photos on the wall were silly pictures of our friends. There we were, serving cheap hash from a can to a man accustomed to, and worthy of, dishes from the finest chefs.

But one day Tod challenged us. With a frustrated sigh, he pointed at the wall of tacked-up photos and asked us one simple question: “Who is the audience for these pictures?” In other words, if we aspired to be artists or creative professionals, and some of us did (like me), why would anyone care about such mediocre photographs?

When it was clear that we didn’t know, and after a few moments where the silence hung heavily in the room, Tod started in on what turned out to be a lengthy story, part auto-biography, part years-in-the-trenches tale of how hard it is to be an artist, to create things for people who don’t care one whit about you, or your ideas, or your creative output. He told us how important it was to know who our work was for, and then to aim our creative output right at them. Even then, the chances of success were marginal. Our best hope was to hone and refine and tune a message so that the intended audience would be willing to receiving it and that a connection might be made through the work.

When he was finished with his half-monologue, half-soliloquy about twenty minutes later, he was clearly affected by the remembrances of his personal story. He was no longer frustrated or sighing, and we were all surprised by how much he had opened up about his own years of effort and his struggles to do quality work for his audience. Perhaps he was surprised too. By the time he was done, none of us felt good about the photos on the wall at the moment, but all of us felt we had gone on an emotional journey of sorts. We had learned something.

From that day forward, I have never forgotten to ask this question about my own work: “Who is my audience?” When I sat down to write my book, I thought back on that experience in that photo critique studio all those years ago. I knew that I had a set of stories to tell about writing software at Apple, but I needed to decide who my audience was.

It would have been easy to tell my stories for programmers, to make them a set of inside jokes for coders, to “sing the song of my people”. My editor at St. Martin’s Press, Tim Bartlett, asked me to attempt something else. He wanted me to expand my audience—not only for the good of book sales, although that certainly was a concern—but also because it would be more difficult, and perhaps would yield a more useful end result.

Software is inscrutable to most people who don’t work in the high-tech industry. Yet, software is becoming an increasingly important part of everyone’s life on an everyday basis. What if, Tim asked me, I tried to tell my stories so that people might understand more about how software gets made, what the culture of Silicon Valley is like, and give some insight into the people are who can stare all day at computer screens and make computers do what they do. For the potential readers who actually are programmers, Tim asked me to give them some explanations they can use to explain their jobs—like when an uncle or aunt at a holiday gathering wants to know what you do for a living and how you spend your time at the office.

So, that’s what I tried to do. Who is the audience for my book? Everyone. I tried to make software understandable to people who don’t know the difference between a bit and a byte. At the same time, I tried to give software professionals a few examples they can use to make their job seem sensible and accessible to family and friends.

OK. OK. As you might imagine, I did some more technically-targeted writing in early drafts, and to toss a bone to you programmers out there, here are a few paragraphs I wrote about our porting effort for KHTML… including terminal windows and Unix commands!

— Ken

Computery Remembrances Of KHTML Development

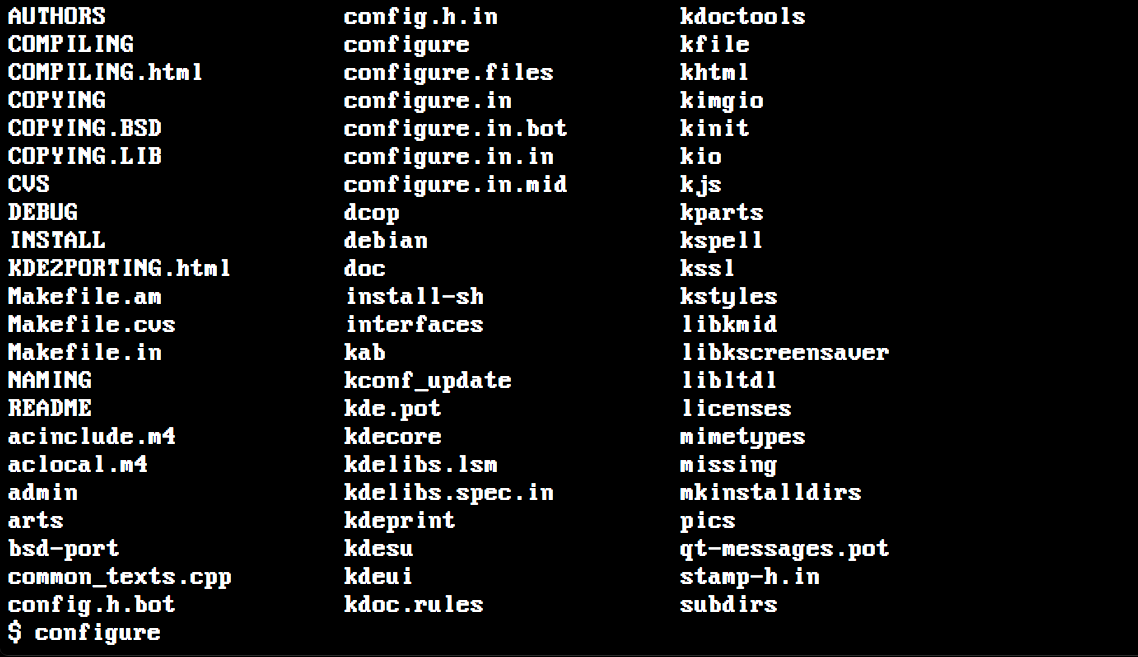

The morning after Richard showed his Konqueror web browser demo, I got to the office early, around 6 am. On my desk, next to my Mac, I set up a white-box PC tower computer, a leftover from my days at Eazel. I wiped its hard disk, installed a Linux distribution, and booted the system. Then, I typed a long train of commands. I downloaded the source code for KDE, the Linux desktop environment which included Konqueror, and I configured the programming environment so I could build it. I can still see the white letters against the black background of my cathode ray tube monitor, monospaced characters with a blinking block cursor in a text-mode console window. It was like a technological vision from days long ago, certainly from before the days when Apple shipped the Mac, which introduced the mouse, and icons, and the graphical user interfaces in to the mainstream. It was as if, to restart my browser investigations in the aftermath of Richard’s demo, there was a requirement to recapitulate the evolution of earlier forms of computing, much like how humans go through reptile and fish phases in the womb. To kick off this KDE work right, maybe I should have gone back past text mode to punched cards, or to an abacus, or to tally sticks.

Back not quite as far as that, at Eazel, we had been a GNOME shop, and I had spent the best part of a year trying to make that Linux desktop environment the one to beat. As I sat at my desk at Apple and watched the compiler stream screen after screen of text output as it built KDE from source code, it felt a little naughty to be working with this GNOME competitor. It was like breaking up with a girl, only to turn right around and ask her sister for a date. “Hi. What’s your name? K-D-E? Can I call you Katie?”

One of the main differences in KDE is that its developers had built their own web engine from scratch, an achievement which demonstrated their vision, their self-confidence, their guts, their programming skill. I wondered if the Konqueror developers really had known how hard it would be to build a web engine before they committed to the effort, or whether they started their project with the combination of naïveté and hubris so common among software engineers. I wondered if, at that moment, I was really so different. I still had no idea how hard it would be to make a web browser, but the KDE developers had done it, and here I was, in blissful ignorance, building the source code for it. Once the build was complete, I started KDE. I launched Konqueror. I surfed the web for a few minutes, and I was impressed by how well everything worked. The browser was snappy and loaded web pages quickly.

I reported my morning’s progress to Don, and he was very pleased to hear that everything had gone so smoothly. This KDE downloading and building task was his idea. He thought it was the next logical step after Richard’s demo. He wanted me to see what it was like to work with the KDE source code, and to start finding out how feasible it might be to extract the Konqueror browser from the rest of KDE. Richard’s demo had been an all-up build of KDE, but moving ahead from here, we only wanted the source code for the web engine. Don wanted me to isolate it. If these web engine source code files could be isolated and extracted, then we would copy them over to the Mac and use them as the foundation of an Apple web engine. The answer was all there for me to find in the source code.

And the answer was there. When I returned to my computer after getting coffee with Don, I soon found what I was looking for. It didn’t take me very long at all. After a few minutes of poking around, I spotted two libraries of source code as if they were waiting for me to stumble across them: KHTML and KJS. The KHTML library contained the content portion of a web engine, HTML and the DOM, and a style system, CSS. The KJS directory had a JavaScript language implementation, and this provided the necessary scripting support. These two components of KDE, KHTML and KJS, looked like they made up a complete web engine, everything we needed, a content system, a style system, and a scripting system.

This was very promising, but the next thing I did filled my heart with geeky joy. I went to the command line in a terminal window, and I asked the computer to count the total number of lines in all the source code files in KHTML and KJS, something like this:

> find . -regex ".*[cpp|h]$" | xargs wc -l

In response to this command, the computer would print a report, listing each file which had a name ending with either a .cpp extension, indicating an implementation file written in the C++ programming language, or a .h extension, a C++ header file. Before each file name, the report would list the number of lines in the file, as counted by the word count (wc) program, a program which could also count line-by-line. As a nicety, the wc program kept a running sum of all the line counts for all the files it counted individually. My command took a second or less to run, and at the end, down at the bottom of my terminal window, I saw the result:

…

146 ./khtml/xml/dom_textimpl.h

407 ./khtml/xml/dom_xmlimpl.cpp

142 ./khtml/xml/dom_xmlimpl.h

439 ./khtml/xml/xml_tokenizer.cpp

129 ./khtml/xml/xml_tokenizer.h

122582 total

I looked at it again. 122,582. Less than one hundred and twenty-three thousand lines. I scrolled back up in the terminal window to make sure my command looked alright, and that it wasn’t missing anything. It wasn’t. My command was correct. The report included all the source code files in KHTML and KJS. The line count was right. I felt an odd mixture of excitement and relief. This was great news. I found the source code which contained the key elements of the Konqueror web engine, and I determined that it was less than one-tenth the size of Mozilla. Geeky joy, indeed.

If you liked this alternative retelling of the early days of Safari, tell your friends to buy a copy of Creative Selection, and then point the more nerdish crowd back here so they can share in the geeky joy. Got a comment? Find Ken on Twitter. In the meantime, happy hacking!